Astronomers have identified the first exoplanet with a layered atmosphere like Earth’s. However, make no mistake: this world is unlivable. It is also one of the most extreme ever discovered.

Several observatories have led to the discovery of thousands of exoplanets in the galaxy. What astronomers would like now is to characterize some of these worlds. With this in mind, the European Space Agency (ESA) launched its CHEOPS (CHaracterising ExOPlanet Satellite) mission in December 2019. By focusing on the tiny variations in luminosity of stars already known to host one or more worlds, this observatory allows it is then up to researchers to define the properties of these worlds with more precision.

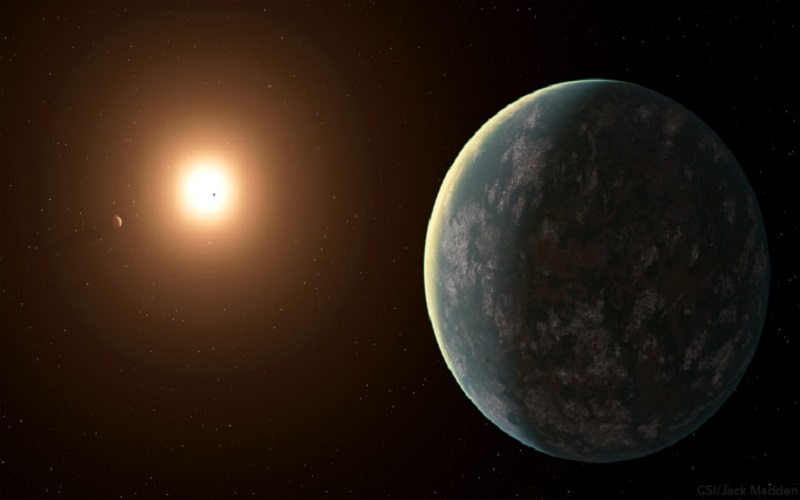

A few months ago, CHEOPS had its eye on the exoplanet WASP-189b, a “hot Jupiter” discovered in 2018. As a reminder, these worlds are planets similar to Jupiter, but evolving very close to their star.

322 light-years from Earth, this planet orbits less than 7.5 million kilometers from its star, a blue giant named HD 133112. For comparison, that’s about twenty times closer than Earth does. is from the Sun. Naturally, this proximity is not without consequences. According to data from CHEOPS, the surface temperature on the “day” side (WASP-189b shows only one side of its star) is estimated to be around 3,200°C. This planet thus presents itself as one of the hottest gas giants ever recorded.

A priori, WASP-189 looks nothing like our planet, but our two worlds still have one thing in common: a complex atmosphere in superimposed layers.

A complex envelope

As part of this work, the researchers are not relying on CHEOPS, but on the observations collected in 2019 by the HARPS (High Accuracy Radial Velocity Planet Searcher) instrument, from the La Silla observatory (Chile), during three passes of the planet in front of its star.

By observing the ring of light surrounding the planet’s shadow, astronomers can study the composition of its atmosphere, with each molecule absorbing a different wavelength. These detected chemical fingerprints are also influenced by the Doppler effect. In their analysis, the researchers then pointed to slightly different Doppler effects between different chemicals, suggesting that they move differently through the atmosphere.

“We believe that strong winds and other processes could generate these alterations,” says Bibiana Prinoth, from Lund University. “And because the fingerprints of different gases have been altered in different ways, we believe this indicates that they exist in different layers, similar to the fingerprints of water vapor and ozone on Earth would appear differently, as they mainly occur in different atmospheric layers.”

Until now, astronomers assumed that the atmospheres of exoplanets only offered a uniform layer. These results demonstrate that even the atmospheres of intensely irradiated gas giant planets can develop complex three-dimensional structures. In the future, the James Webb Telescope, which has just parked around the Lagrange point 2, will be able to conduct this type of analysis by targeting other nearby planets.