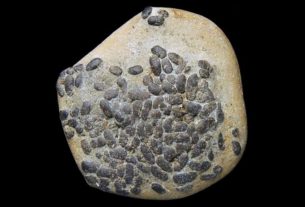

The remains of a nearly complete dwarf emu egg – a bird that went extinct about 200 years ago – have been unearthed in a sand dune on an island between Australia and Tasmania. Surprisingly, and despite its “small” build, this bird’s egg was almost the size of an ordinary emu egg.

The discovery is unique, says Julian Hume, a paleontologist at the National History Museum in London. And for good reason, it is the only known almost complete egg of Dromaius novaehollandiae minor found on King Island. The dwarf emu, which was roughly half the size of the mainland emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae), the only surviving emu, is believed to have disappeared around 200 years ago.

A surprisingly large egg

The islands off southern Australia were once home to three subspecies of emus: the smaller Tasmanian emu (D. n. Diemenensis) and two dwarf emus, the King Island emu and the King Island emu. Kangaroo Island (D. n. Baudinianus). During the last ice age, all of these islands were connected to the Australian mainland. The melting ice, which took place around 11,500 years ago, then took on the task of isolating them by raising the sea level. From then on, these emus quickly shrunk to adapt to the available resources (island dwarfism).

As part of this work, the researchers compared the dimensions of the egg with those of thirty-six emus eggs from mainland Australia, six emus from Tasmania and a specimen from Kangaroo Island. Femurs of each species were also analyzed.

It then emerged that, despite the differences in size between species, that of their eggs was remarkably similar. The egg of a mainland emu weighed an average of 0.59 kilograms for a volume of about 539 milliliters, while the King Island dwarf emu egg weighed 0.54 kg for a volume of 465 milliliters.

Little ones ready to fend for themselves

To explain these measurements, Julian Hume suggests that chicks of this subspecies must be large enough to maintain sufficient body heat and be strong enough to immediately forage for food after hatching. The same evolutionary phenomenon is observed today with the kiwi, a bird endemic to New Zealand that lays eggs as large as its body (up to 25% of the mother’s body).

In this way, the little dwarf emus of King Island had perhaps a better chance of survival against predators. At the time, they mostly had to contend with the Dasyurus, a small carnivorous marsupial. Eventually, the species went extinct just five years after humans first arrived on the island.